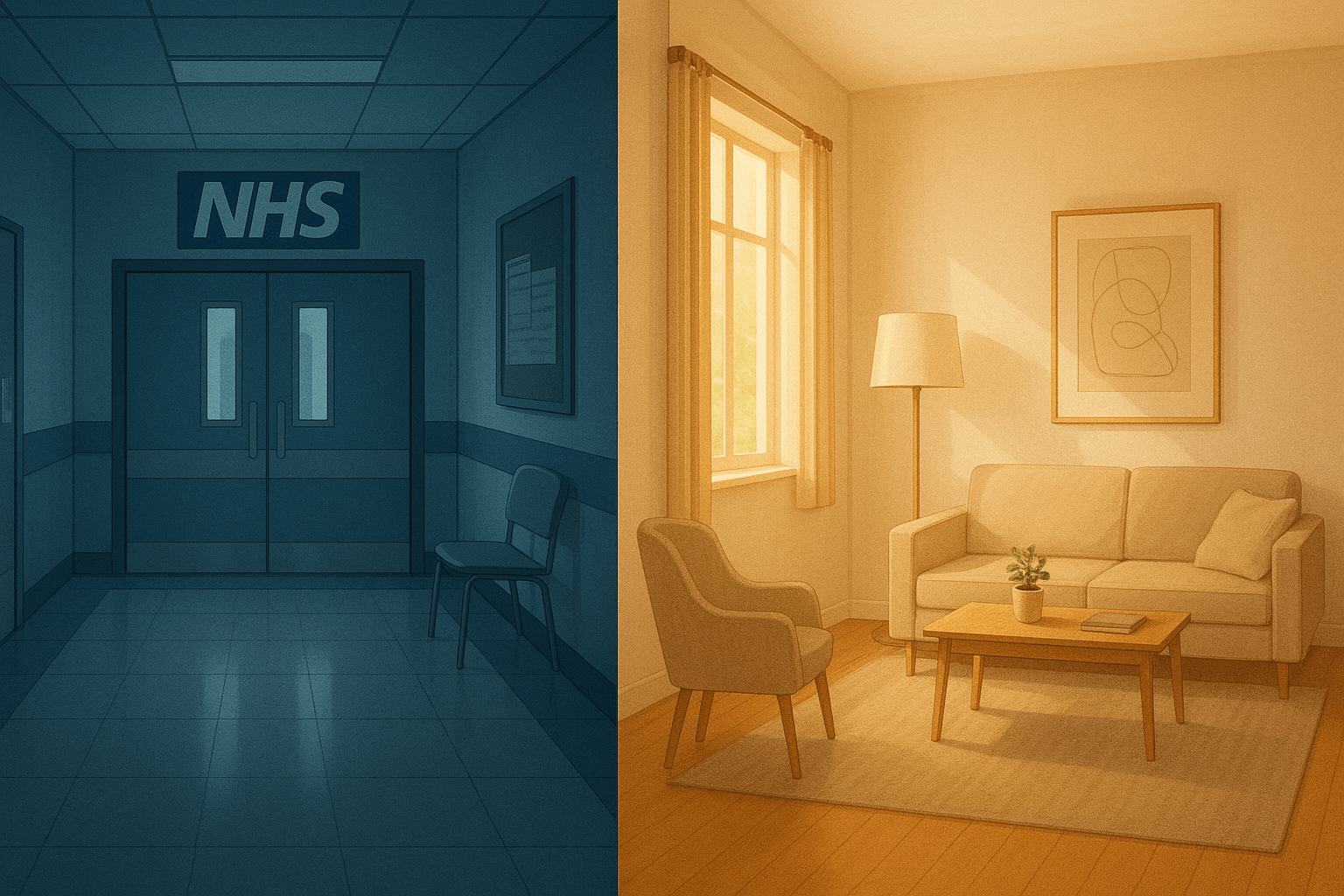

The UK has long nurtured a quietly heroic belief: that through the NHS we receive healthcare as a citizen’s birth right. We imbue it with a sense of sacredness, assuming that hospitals, GPs, even mental health care, should be “free at point of use”. Yet increasingly, that assumption is fraying under strain. In 2025, more people are being priced out of private therapy, but that cost is not arbitrary. It is rooted in rigorous training, rising costs of practice and a health system buckling under demand.

The NHS is overwhelmed and mental health waiting lists grow

Let’s begin with the terrain. We may love the NHS, but it is in a state of under-resourcing and overload. For those seeking mental health care, waiting times are frequently excessive. New analyses show that people are eight times more likely to wait over 18 months for mental health treatment than for elective physical treatments. The human cost of this disparity is staggering.

One survey found that 80% of people waiting for community mental health support experienced deterioration in their condition during the wait. Another study tracking the longest waits found that some people waited 727 days for community mental health care, while elective physical health waits averaged 315 days. These aren’t just statistics, they represent lives suspended, suffering prolonged, potential unrealised.

At the same time, NHS Talking Therapies (formerly IAPT) are under targets. The standard dictates that 75% of patients should have a first appointment within 6 weeks of referral and 95% within 18 weeks. In January 2024, 92.1% of referrals met the “less than 6 weeks” threshold, which sounds encouraging, but that data covers only those who complete a course of therapy. The backlog, unmet need and dropouts remain under the surface, invisible in the metrics yet painfully real to those experiencing them.

When mental health support is delayed, the brain and body pay the price. Persistent stress elevates hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity, raising cortisol, disrupting sleep, impairing hippocampal plasticity, blocking emotional regulation pathways and deepening neural entrenchment of maladaptive circuits. In trauma work, timing matters: early intervention reduces the embedding of maladaptive schemas and neurobiological dysregulation. The longer someone waits, the more entrenched pathways of fear, hypervigilance or dissociation can become.

In that vacuum of timely care, many people turn to self-help books, apps (some helpful, many not), or informal supports. But when systemic services lag, private practice becomes the safety valve. Yet when people see therapy costs soaring, many hesitate. They resist paying for what they believe should be free.

“Healthcare should be free” versus “therapy costs money”

In the UK, we are steeped in a cultural narrative: healthcare is a public good, funded by taxation. Most citizens never see the mechanics, how budgets are stretched, contracts negotiated, staff burned out, buildings left unmaintained. When someone mentions “paying” for healthcare, many hear betrayal, as though profit, greed or elitism have crept into the sacred NHS.

Compare that with the US (or other insurance based model systems). There, private psychotherapy is longer established as part of health insurance or out-of-pocket care. The idea that a clinician’s service comes with monetary value is more normalised. In the UK, that normalisation is still emergent, still contested, still uncomfortable.

The dissonance is real. Clients often feel conflicted: “Should I pay for therapy when the NHS is supposed to cover mental health?” “Am I admitting failure by needing private care?” “What does spending money on therapy say about me?” These are emotional and moral loadings placed on a service that is, at heart, about healing and personal growth.

To shift that mindset, we need a narrative pivot. We must reframe therapy not as a luxury indulgence, but as a vital, high ROI health investment. We have to help people see that paying for therapy is like paying for dental care or physiotherapy: you hope not to need it forever, but when you do, the quality of it matters.

What it really costs to become, and be, a good psychotherapist

To understand why therapy fees rise, one must peek behind the curtain. Let me walk you through the economics of training, practice, maintenance and why these realities must reflect in fees if clients are to receive safe, competent, deeply ethical care.

Training and qualification costs

Many psychotherapy training programmes (such as postgraduate diplomas and master degrees) cost £8,000–£9,000+ per year. As an example, the Minster Centre charges around £8,767 for a PG Dip course starting in 2025. During training, students must undertake personal therapy, often paying £55–£75 per session or more on a weekly basis, depending on the therapist. Trainees also pay for supervision, guidance from experienced clinicians, often at extra cost.

Training organisations may require payment of membership fees to bodies such as the UKCP. Full clinical membership is approximately £302. Yet even these professional bodies face pressures: UKCP has reported a staggering 2,900% increase in professional liability insurance premiums. There are many hidden extras: travel to training venues, placement work travel, materials, textbooks, administrative overheads, venue hire, insurance and infrastructure.

Training is not a “cheap hobby”. It is years of investment, financial, emotional, intellectual.

Post-qualification maintenance

Even after qualification, therapists must maintain professional development: ongoing supervision, CPD courses, conferences, reading, peer consultation, insurance, professional memberships, office rent, heating and utilities. Many therapists run their practice as sole traders or small businesses, they are responsible for tax, marketing, managing cancellations, record keeping and indemnity insurance.

As noted, UKCP has faced skyrocketing insurance costs, which practices may need to absorb or pass on to clients. Inflation, cost-of-living rises, rent increases, utility bills, all these squeeze private practices too.

When you are paying for therapy, you are not only paying for the hour with the therapist, but for decades of education, supervision, infrastructure, ongoing ethical safeguarding and business overhead.

The psychology of fair pricing

There’s also a psychological threshold: clients often resist paying more than a certain amount, so therapists are squeezed between delivering high quality care and keeping fees “acceptable”. Many therapists under charge relative to their skill and risk in order to remain accessible and that is not sustainable long term.

The neurobiological and medical “value” of timely therapy

It’s not just warm, fuzzy talk: there is a growing neuroscientific and psychophysiological basis for early, high-quality psychological intervention.

- Stress regulation and HPA axis healing: Prolonged stress dysregulates cortisol rhythms, causes receptor desensitisation, impairs hippocampal neurogenesis and heightens amygdala reactivity. Psychotherapy, especially modalities attuned to regulation, safety, embodiment, can recalibrate these systems through the process of attachment, co-regulation and somatic regulation.

- Neural plasticity: The brain remains plastic into adulthood; therapy helps rewire neural circuits (those tied to fear, shame, self-talk, emotional regulation). The earlier you intervene, the less the maladaptive circuits consolidate.

- Memory reconsolidation and trauma processing: Especially in trauma work, therapy can facilitate reconsolidation, where traumatic memory traces are updated in a safer context, reducing threat responses. Delays in therapy can mean that traumatic neural pathways grow more fixed.

- Interoceptive regulation and vagal tone: Many psychotherapies incorporate body awareness, somatic regulation, breath, vagus nerve stimulation, supporting autonomic balance, reducing hyperarousal or dissociation.

- Biopsychosocial feedback loops: Mental health is not separate from immune, endocrine and metabolic health. Untreated chronic stress contributes to cardiovascular disease, inflammation, insulin resistance and worse physical health outcomes. Thus, investing in mental health can arguably reduce downstream medical burdens.

If we cast therapy not as a “nice-to-have”. but as part of preventive medicine, the ROI becomes clearer: fewer crises, relapses, comorbidities, emergency usage, hospitalisations and lost productivity.

Framing therapy as investment, not indulgence

To shift mindset, we need metaphors and reframes.

- Therapy as maintenance: Just as you service a car, brush your teeth, maintain your physical health, therapy is part of your mental health hygiene. You don’t wait for breakdowns; you intervene before cracks deepen.

- Therapy as precision medicine: General life advice is like over-the-counter medicine. Therapy offers individualised, tailored insight, emotional attunement and treatment.

- The long game ROI: A few months of therapy may prevent decades of relapse or chronic suffering. That one hour a week may ripple into healthier relationships, better work performances, less medical burden.

- Scarcity mindset vs value mindset: Many clients say, “If I spend this money on therapy, what else do I give up?” That internal argument is real. But I often say to clients: “If you can sacrifice for something momentary, why not sacrifice for something lasting?” That pair of shoes, that holiday splurge, it’s a temporary fix. Experiencing therapy’s gains endures much longer.

- Tiered models, sliding scales, packages: Therapists can adopt creative pricing: blocks of sessions, concessions, shorter models, package deals. This provides flexibility while still honouring value.

People need to see that paying for therapy is not “paying for help”, it is “investing in health, autonomy, growth, freedom.”

Invitation to a new mindset

I don’t pretend this is easy. Many people will resist paying for therapy when they believe it “should” be free. Many will feel guilt, shame or internal conflict. But as a UKCP accredited person centred psychotherapist, I believe in choice, autonomy and dignity. If a client can choose where to allocate finite resources, choosing therapy can be an act of radical self-care, of holding one’s own mental health as sacred.

What if we began to frame therapy appointments in the same breath as buying quality food, paying for dental care or physical therapy? What if a conversation started: “I pay for my therapy not because I’m broken, but because I matter.”

And for those who can’t yet afford full private rates, let us build systems of support, subsidies, and alternatives, but not at the expense of devaluing the work of the therapist. Because when therapists are forced to undercharge or operate unsustainably, quality, safety and accessibility suffer.

Health is never free, it is paid for, somewhere, by someone, in time, energy, resources. The NHS has been a stunning social achievement, but its limits are visible now. Private therapy is not the enemy. It is part of a shift we are negotiating: from always expecting free care, to recognising that some care demands investment. That if we pay the real cost of therapeutic expertise, we honour not just symptom relief, but healing, resilience and restoration.